By Triangle Day School

October 10, 2019

Professional development days offer a unique gift during the sprint from late August to early June – the gift of time. Yesterday, faculty and staff came together for an energizing day of learning. We began with a review of emergency medical procedures during a training and recertification in CPR and First Aid. Following this, teachers met in groups to discuss a variety of curricular initiatives, including our new literacy program in Lower School.

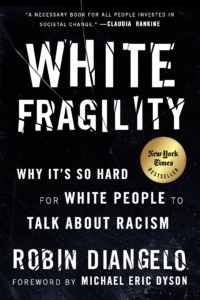

After a hearty lunch provided by sixth-grade parents (thank you!), we met once again to discuss two books from our summer reading: White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, and Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. As the titles suggest, these books fit nicely with our effort to identify and reduce our own blind spots, develop awareness, and build an inclusive environment where all persons are supported, valued, and engaged.

After a hearty lunch provided by sixth-grade parents (thank you!), we met once again to discuss two books from our summer reading: White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, and Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. As the titles suggest, these books fit nicely with our effort to identify and reduce our own blind spots, develop awareness, and build an inclusive environment where all persons are supported, valued, and engaged.

Blindspot begins with the understanding, confirmed by countless studies spanning sociology, psychology, and economics, that “the social group to which a person belongs can be isolated as a definitive cause of the treatment he or she receives.” Despite our conscious commitment to egalitarianism, the authors point out that the human mind “works automatically, unconsciously, and unintentionally,” often registering preferences in attitudes involving race, sexual orientation, age, and a host of other factors.

Blindspot highlights the Implicit Association Test, an assessment tool created by Anthony Greenwald that has revolutionized our knowledge and insight in these areas. The test is surprisingly accessible and easy to take. In fact, all teachers took one of the tests yesterday.

Blindspot highlights the Implicit Association Test, an assessment tool created by Anthony Greenwald that has revolutionized our knowledge and insight in these areas. The test is surprisingly accessible and easy to take. In fact, all teachers took one of the tests yesterday.

As the test has grown in popularity, researchers now have millions of data points to analyze. The IAT reveals that a majority of people have an “automatic preference” for white relative to black, young as opposed to old, as well as various gender-related stereotypes (most associate men with work and women with family, for example). It seems that “whether we want them or not, the attitudes of culture at large infiltrate us.”

The authors point to the history of symphony orchestras to illustrate the implications of these automatic preferences. In the 1970s, women constituted approximately 20% of new hires in orchestras across the country. Few seemed concerned by this. After all, the world’s top (or best known) instrumental virtuosos were all men.

During that decade, orchestras began tweaking their hiring procedures. The live audition remained the key component, but instrumentalists began performing behind a screen. Now, of course, those auditioning were audible but not visible. In the years that followed, the percentage of women hired doubled from 20% to 40%.

It seems that most of us are more susceptible to automatic classification and judgment based on stereotypes than we would like to believe. The elegant design of the IAT brings our hidden biases into focus. And then what? Armed with this knowledge, we must at a minimum ensure that our unconscious thoughts do not translate into behaviors and actions. Additionally, we can seek out experiences that might help reduce or reverse the “mindbugs” nestled in our brains.

To learn more about the science behind and implications of the IAT, watch this interview with Mahzarin Banaji, one of the authors of Blindspot.

Doug Norry

Head of School